For a novelist, visualizing a character – bringing them into focus, learning who they are, and what makes them tick – is absolutely essential. Readers don’t read our books because they fell in love with the plot twists. They don’t seek out a book because they love murder, or war, or the scientific concept that makes a book “science fiction.”

They read our books because they fall in love with our characters.

At least, we writers desperately hope they’ll fall in love with our characters. Or anyway that they’ll be fascinated by them. Because if they don’t care what happens to our characters, all of our clever plot twists have no meaning. The murder or the war is just butchery or mayhem. That ingenious science fictional concept we invented might only make them say, “Oh. Well, that’s kinda interesting. But what’s happening on Tik Tok?”

No, the charactersare key. They’re the point of the story, as far as most readers are concerned. Their trials, their passions. The dangers they face, the risks they brave. And, most importantly for the core archetypal function of literature, the solutions they devise for their terrible problems.

|

| About a year ago, G.S. Norwood wrote about one of McCullough’s books. (See credits below). |

Characters are Everything

When I was first learning to write, people sometimes asked, “is this a plot-driven story, or a character-driven story?” I have come to the conclusion that it’s a literature-analysis question making a point that is irrelevant to the way most readers of fiction engage with the stories they read. For me, every story is “character-driven.” It has to be, or it fails in fundamental ways.

That’s why it’s really important for a writer to know their characters. But it’s all very well and good to say that. How does one go about doing that? Especially when the person one is trying to get to know is an imaginary person in our own head? Because I am here to tell you, they don’t spring fully-formed from my forehead, Zeus-and-Athena-style.

No. Not even a little. Visualizing a character in all their dimensions takes effort and time.

Some writers “interview” their characters. They ask questions such as the character’s favorite color, their favorite food, music, and so on. I’ve tried that. It can be interesting, and occasionally enlightening. Some writers create elaborate backstories or dossiers on their major and semi-major characters. I’ve done some of that, too. And I always try to keep track of how tall, how heavy, eye color, age, and important skills, relationships, and so on – written down in a place I can remember! You might not believe how many times I’ve caught myself and said, “Wait! How much does Rex weigh, again?” (130 kilos, when in good shape). Visualizing a character only works for my readers if I’m consistent.

|

| Possibly the most influential author in my own childhood, Alexander’s words continue to be true for me, whether I’m the reader or the writer. (See credits below). |

How Best to Learn a Character?

I can only tell you what works for me. Sometimes I’ll get to a place in a story where I need someone to do something. Then a new person who is exactly when and where I need them sometimes steps forward. They do what the story needs, but add their own little personal touch to the way it’s done. That’s when visualizing a character is fun and easy. Occasionally I may decide that person needs a promotion to a bigger part in the story! (This is my “pantser” side emerging).

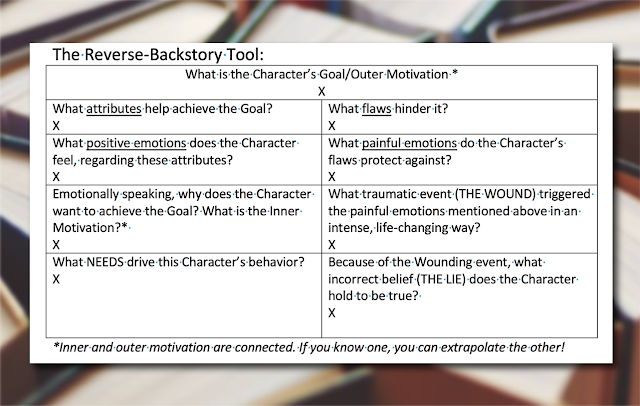

More often I’ll know, going into the story, that certain characters belong onstage. I’ll already know some basic aspects of those characters, but not enough. That’s when I need help visualizing a character. I like to use techniques such as the Character Flaw Pyramid or the Reverse Backstory Tool (see below). If this is getting too technical for you, feel free to skip over this part.

But for the writers and reviewers in my audience, I’ve found these very helpful for developing the Protagonist and Antagonist characters. I’ve also used them for supporting characters who have their own, smaller story arcs within the book.

|

| From Jan’s “Writing Techniques” notes; source unclear. (See image credits below). |

|

| From Jan’s “Writing Techniques” notes; source unclear. (See image credits below). |

I got these . . . somewhere, at some point in the last five years. Probably/possibly they came from one or more of my friends (I hang out with a lot of writers. Possible sources include Dora Furlong and Lynette M. Burrows, but I really don't remember. You might enjoy their books, though!). And I have no idea who, among all the many tutors, online courses, blogs, or writing gurus, originated them. I just know these tools work for me. But there’s also another important method in my toolbox.

Visualizing a Character . . . Literally

When I say I’m visualizing a character, I also mean that literally. I’m an artist, so I think visually and spatially. I make maps. Create floorplans. Collect visual reference photos, and make my own drawings. But I’ve never had the “illustrator” gift. Non-artists may find that confusing, but in my experience not every artist is cut out to be an illustrator. It’s a specific subcategory of skills that I’ve always wished I had! But the ability to create really awesome illustrations is just not a gifting I’ve received or been able to develop (Lord knows, I’ve tried!).

All the same, I am both lucky and blessed. I have many friends who are outstanding illustrators, richly endowed with that gift I wish I had. And, here in the later decades of my life, I also have been blessed with the ability to hire them to do what I can’t.

This means my longtime friend Jody A. Lee has made gorgeous covers for the first two novels in the XK9 Trilogy. If you’ve been following this blog since last summer, you may remember reading The Story Behind A Bone to Pick’s Cover. It also means I could commission some early character-and-tech-development images from artist and game designer Jeff Porter. And I could ask the illustrator Jose-Luis Segura to help me visualize two characters, Mac and Yo-yo, whom I intend to feature in a future story.

And it means I could embark on a long and ongoing creative collaboration with my good friend Lucy A. Synk.

Visualizing a Character with Lucy A. Synk

I chronicled my collaboration with Lucy to create the cover of my novella The Other Side of Fear on this blog almost exactly two years ago, in March 2020. Lucy was literally Rex’s first fan. She’s a well-regarded professional artist with years in the fantasy and science fiction world, a background in natural history museum murals, and a burgeoning fine art career. She’s about to unveil a brand-new website, so here’s hoping this link redirects properly. If you’re on Facebook, you also can see (and “Like,” if you’re kindly inclined) her Lucy Synk Fantasy Art page.

Last winter, she helped me visualize The Orangeboro Pack. She painted all ten XK9s from my books, both as head-and-shoulders portraits and in full-body action poses. I’ve used those a lot, especially in my monthly newsletter.

|

| Top row L-R: Razor, Elle, Crystal, Petunia, and Cinnamon. Bottom Row L-R: Scout, Victor, Tuxedo, Shady, and Rex. (All paintings are ©2020-21 by Lucy A. Synk). |

This winter, her project has been to start visualizing the humans in my stories. Since she’s already posted the first two paintings from the new series on her Facebook page, I’ll show them here, too.

|

| Here are the finished paintings, L-R: Hildie at Work and Hildie on a Balcony in a Saree. (Artwork © 2022 by Lucy A. Synk). |

Next week, I’ll talk about our ongoing collaborative efforts, and the developmental stages we went through when we were visualizing a character named Hildie Gallagher for these two paintings.

IMAGE CREDITS

Many thanks to Quotefancy, for the David McCullough quote. You may remember that G. S. Norwood blogged about one of McCullough’s books in this space about a year ago. And thank you very much, AZ Quotes, for the wisdom from Lloyd Alexander.

As noted in the post, Jan has no clear idea of exactly where the “Character Flaw Pyramid” or the “Reverse-Backstory Tool” came from. But the photo of the hands holding question-marks up in the air is definitely by "rawpixel," via 123rf. And the pattern of books background certainly came from Madison Butler on LinkedIn and her “Unicorn Nuggets” newsletter. Many thanks to both!

The digital painting of Pamela Gómez and the sketches of an EStee, along with the designs for collar-mounted vocalizers, are all © 2016 by Jeff Porter. The digital painting Mac and Yo-yo in Their Workshop is © 2021 by Jose-Luis Segura. The ten XK9 portraits are © 2020-2021 by Lucy A. Synk. The two new oil paintings of Hildie Gallagher are © 2022 by Lucy A. Synk. Jan enjoyed every minute of those collaborations, and looks forward to doing it again! All montages in this post were designed and assembled by Jan S. Gephardt.

No comments:

Post a Comment