By Jan S. Gephardt

I love both real and fictional space stations. Anyone who’s read my books, or the blog posts I’ve devoted to this topic will probably roll their eyes and say, “No. Really?”

Yeah, really. You got me. I love the whole idea, and I’m endlessly fascinated by the many visions of what a space station—or space habitat—could be.

Why? I’ve enjoyed science fiction for decades. When I was a kid I thought of sf books as “the books that give you stuff to think about.” (Perhaps I should clarify: I considered that a good thing). I was interested in how we humans might someday live somewhere other than on Earth.

Throughout human history, there’s always been a healthy exchange of life influencing art, which then influences life. In the case of real and fictional space stations, that’s definitely true.

When it comes to space exploration, the “art part” came first. From flip phones to satellites to space stations, visions cooked up by science fiction writers, artists, and filmmakers electrified and inspired several generations of 20th-Century rocket scientists, engineers, and designers.

|

| Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot, stands on the surface of the moon near the leg of the lunar module, Eagle, during the Apollo 11 moonwalk. Astronaut Neil Armstrong, mission commander, took this photograph with a 70mm lunar surface camera. (NASA/Wikimedia Commons). |

Living Somewhere Other than on Earth

I was a schoolkid when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon on July 20, 1969, so I remember the excitement (and the setbacks) of the Space Race.

But that timing means more than just that I’m now “older than dirt.” It means I was an idealistic art major who embraced the environmental awareness of the 1970s. Concerned as I was about Earth’s future, I hated dystopian sf stories in which humans left a dying, poisoned Earth for supposed “greener pastures” (to, um, . . . poison and kill those, too? Great legacy, humans!).

Back then, a lot of us feared the “population explosion” that was supposedly going to devastate the planet. This was the era when Harry Harrison wrote his 1966 novel Make Room! Make Room!, from which the 1973 movie Soylent Green was adapted.

Space habitats interested me, but not as places to flee after the earth dies. I was interested in their potential to ease some of the environmental pressure on our natal planet.

|

| Earthrise, taken on December 24, 1968, by Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders. (NASA/Wikimedia Commons). |

Digging into the Details

I wasn’t the only one interested in what were then called “Space Colonies.” NASA commissioned multiple studies into the feasibility of space-based habitats for humans.

Rana Station’s design origins came from those studies. The idea is a surprisingly old one, but interest at NASA proliferated, starting in the 1970s. The differentiation between real and fictional space stations got kinda thin when the ideas came from the space agency.

That is, until a Senator named William Proxmire made a big fuss about them as a waste of taxpayer money, and gave the programs a Golden Fleece Award. Publicly humiliated, the powers-that-be swiftly shut down that line of inquiry.

I felt wary of the “space colonies” idea, in any case. Colonialism was rightfully beginning to receive a lot of pushback. The idea of being a colonist dependent on corporate control smacked way too much of being trapped in a “company store” scenario.

|

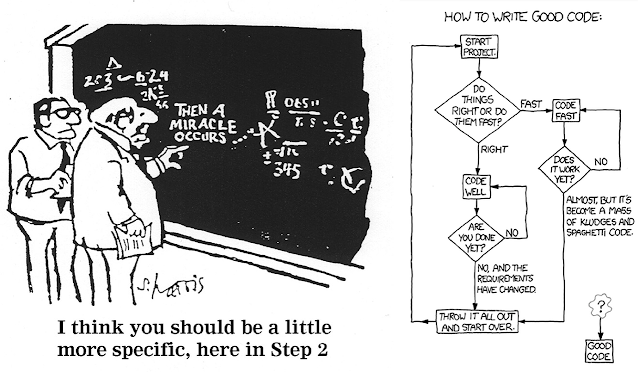

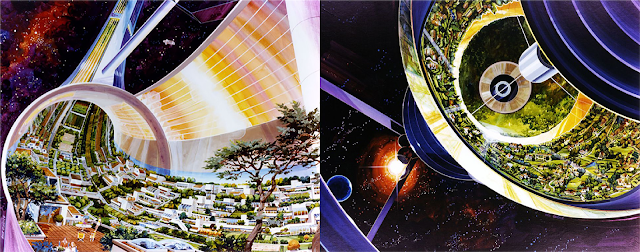

| Two classic paintings by Rick Guidice, showing cutaway views of a Stanford Torus and a Bernal Sphere. (NASA via Space .com). |

Real and Fictional Space Stations

“Space colonies” may have received a decades-long black eye, but we clever apes didn’t stop thinking about space. Nor have we stopped studying it, nor longing to explore space in person, as well as with our robots.

And in the name of exploring it in person, we started building space platforms where we could experiment. When I went into high school, the only kind of space stations anywhere that we knew about were those in science fiction.

The year before I graduated, the Soviet Union successfully launched Salyut 1. The early history of the Salyut series, Almaz (Soviet military) stations, and US Skylab included a lot of problems. Even so, ever since April 19, 1971 we have lived in an age of both real and fictional space stations.

I’m not sure it’s possible to explain how huge that step still seems. Nor my pleasure that I was privileged to (vicariously) see it happen.

|

| Early space stations, L-R: Salyut 1, a rare photo of the first-ever-space station; Skylab; Mir. (See credits below). |

Real Space Stations

The earlier stations weren’t as large or long-lived as the later Mir (1986-2001) and the International Space Station (commissioned by President Reagan in 1984 the first pieces went up in 1998, and development is ongoing to this day.

Are you old enough to remember when the ISS first went up? Or has it always been out there, hanging out in space since you’ve been alive?

Have you ever glimpsed it passing overhead? I’ve seen it—or at least I've thought I saw it—several times. But I usually can’t, because I live in a brightly-lit city with lots of trees. That means light pollution and an obstructed horizon. Thus, even when it’s a clear, cloudless night, station-spotting is a challenge. But when I can glimpse it, I’m always delighted.

Life Influences Art

The conversation between real and fictional space stations continues. Rana Station and I owe a long string of debts of gratitude to the International Space Station.

I’ve watched hours of videos showing the inhabitants of the ISS demonstrating various aspects of living and working in microgravity. I hope that’s helped me create more realistic depictions of things that happen in and around Rana Station’s Hub.

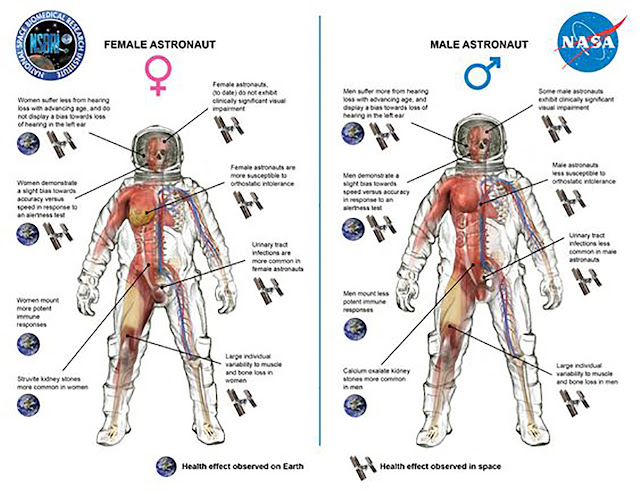

It’s from NASA information that I began to learn about the physical havoc human bodies undergo in any environment that strays too far from Earth-normal gravity.

These findings are the basis for my novels’ limitations on the hours one may spend “up top,” in the microgravity of Rana’s Hub. There are set lengths of time beyond which characters are not allowed to work in microgravity. These are my best guesses, based on what I’ve been able to find in available literature.

|

| This diagram shows key differences between men and women in cardiovascular, immunologic, sensorimotor, musculoskeletal, and behavioral adaptations to human spaceflight. (NASA/NSBRI). |

Lessons from a Real Space Station

Making babies in something other than Earth-normal gravity? I find it hard to swallow the idea that we could do that without danger to both mom and baby (it’s hard enough, here on earth!). Mouse sperm is one thing, but there haven’t been nearly enough studies of the entire process and long-term effects, even in smaller animal species, to reassure me.

Meanwhile, the bottom line is clear, based on more than two decades of research (including a certain fascinating twin study)on the ISS. If we ever want to live and produce future generations any place besides on Earth, we’ll need to do one of two things.

Either we must change our biology, or we must create non-terrestrial habitats that support the biology we’ve got. There’s already ample science fiction that explores either choice. Art points to problems and opportunities with each direction.

I imagine genetic modifications may form a part of our future. But on the whole, I’m betting we’ll prefer the second option, and build to suit our biology. The "conversation" between real and fictional space stations continues!

IMAGE CREDITS

I owe a ton of thanks to NASA for the vast majority of the imagery in this blog post. Not only do they have an inside scoop on “all things space,” but their imagery is blissfully in the public domain (and also my blog posts normally fall under the “fair use” exclusion).

I also owe a massive debt of gratitude to Wikipedia and the Wikimedia Commons, which provided easy-to-find source information for the photos I used. Makes giving credit where credit is due lots easier!

Specifically, the MOON LANDING PHOTO of Buzz Aldrin by Neil Armstrong is courtesy of NASA, NASA Image and Video Library, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. The iconic "EARTHRISE" photo, taken by Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders is courtesy of NASA, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The NASA CUTAWAY VISUALIZATIONS montage features two paintings by Rick Guidice: Cutaway views of a Stanford Torus and a Bernal Sphere from the mid-1970s. Via Space.com.

Credits for the photos in the "EARLY SPACE STATIONS" montage: Salyut 1, an extremely rare photo by Viktor Patsayev (fair use), via Wikipedia. Final Skylab Flyaround, by crew of Skylab 4, courtesy of of NASA, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Mir, from the Space Shuttle Endeavour, courtesy of NASA, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The video about the assembly of the International Space Station components was created and published by ISS National Laboratory, and shared via YouTube. The "Women and Men—In SPACE!" infographic is courtesy of NASA and NSBRI, the National Space Biomedical Research Institute. Many thanks to all!