By Jan S. Gephardt

After I finished What’s Bred in the Bone and published it in 2019, I thought writing A Bone to Pick would be lots easier than writing the first book in the Trilogy. After all, I had an outline. I had scenes, cut from the first novel, all ready to go into the second one. It was partly written already! I should easily have it ready to go by 2020. A year, maybe 18 months, tops, because I know I’m a slow writer. But seriously. What could possibly go wrong?

Right? Easy-peasy!

Except, not so much. I published What’s Bred in the Bone (accidentally early) at the very end of April, 2019. I’ve now passed the 2-year anniversary, and I’m still waiting for the Brain Trust to deliver final thoughts on A Bone to Pick. So, what the heck happened?

|

| Cover artwork for What’s Bred in the Bone is © 2019, and artwork for A Bone to Pick is © 2020, both by Jody A. Lee. |

As much Room as it Takes

I learned a lot of things about my craft while writing A Bone to Pick, for one. I also ran up against an immutable “natural law,” that I used to think was self-indulgent foolishness: a story takes as much room as it takes, to tell it well. Some story ideas naturally fit the “short story” length. Others need more room. Some need a lot more room.

One of my earliest mentors often said “there’s no manuscript that can’t be cut.” He was trying to help me be more succinct, and in that sense he was absolutely right. There is no manuscript that can’t be cut. Often, judicious cutting makes for a much better, more readable manuscript.

But “can be cut” and “should be cut” turn out to be two different things. In a recent blog post, I addressed some of the issues that can arise when a story is cut too ruthlessly. The short version of that post: if you try to squeeze a story into too short a length, you risk destroying the readers’ experience.

First-Draft Blues

I also discovered that in writing A Bone to Pick's outline I had made some leaps of logic that didn’t apply. Turns out, thinking that you have an outline all figured out, and even that you already have the book partly written . . . may or may not be a good thing.

It can be good, because revising is (sometimes) faster than writing from scratch. But it also can be bad, because working from previously-written scenes can partially constrain my thinking and make me miss things. It is likely that many of the partly-written scenes will end up more like writing prompts than recognizable scenes in the final draft.

When I first start working on a plot, For me it’s actually not so much like the Shannon Hale quote about scooping sand into a box that I’ve used in earlier posts. It’s more like I know how I think I want some parts to go.

But there are other parts where it’s a complete mystery.

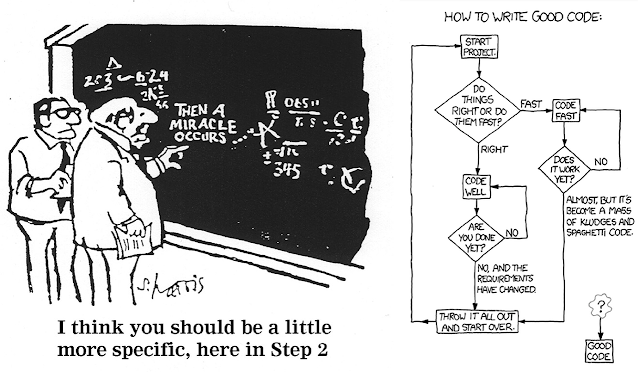

“Then a Miracle Occurs”

| |

Turning a collection of rough ideas into an enjoyable novel involves similar processes. (See credits below).

Quite often, the “complete mystery” parts, the parts where “a miracle occurs,” or where the big question-mark somehow becomes “good code,” turn out to be the best scenes. But getting to them is a matter of feeling one’s way along.

In truth, it’s a difficult process to extrapolate a first draft out of initial ideas, partially-written scenes, and a vague sense of the novel’s general shape.

I’m reminded of the parable of the blind men trying to describe an elephant. Outlining is fine, in its place. But I’m not smart enough to discern all of the realities that writing through the events will reveal to me. I’m lucky to go five chapters before I stumble on something that takes me into new and interesting territory.

To use a different metaphor, it might be a scenic turnout on the “highway” of the novel. It might be a detour that takes me around a terrible wreck or a place where the road becomes impassable. Or maybe it wanders off into the hinterland to a dead end.

A Context-Changing Midpoint

In plot structure, the Context-Changing Midpoint comes very nearly exactly in the middle of the book. Something happens, or the protagonist has an important revelation, and it changes everything.

While I was writing A Bone to Pick, I experienced a Context-Changing Midpoint of my own. Perhaps ironically, it came at what turned out to be almost the exact mid-point in my process of writing this novel.

A member of my Brain Trust told me that the first half of my book was a disaster (she used nicer language). Boring in some places I’d hoped were intense, the pacing dragged, the story didn’t seem to be going anywhere. What was wrong with me? I was a better writer than that, she said (angrily).

The Front End needs a Little Repair

|

| This was kind of how I visualized my project, after a member of my Brain Trust reacted badly to the first half (Green Car Reports). |

Bottom line, however: I needed to trash it. Start in a completely different place, beginning after the part she’d identified as bad.

First reaction: The heck I do! (I didn’t use language that nice).

Second reaction: But this is a member of my Brain Trust! She has excellent judgment!

Third reaction: The heck I do! (I didn’t use language that nice).

Fourth reaction: Oh, damn. She might have a point.

So, I looked at it again. I realized, first of all, that I was really committed to starting the book where I had started it, and including (somehow) the part she’d objected to. She was right about the pacing and drama in that part, however. It was too static.

How do I fix this Thing?

The realization gradually dawned on me that the problematic part wasn’t so much inherently boring, as that I’d handled it badly. For one thing, I’d robbed it of conflict. I’d placed the entire burden of carrying those scenes on one character. But the conflict he confronted was the sort that in most contemporary books demands two point-of-view characters.

Should I break from my original, three-POV pattern in the first book, and add a fourth POV in this one? I forget which Brain Trust member advised me that readers don’t care how many points of view there are. They care if it’s a good story.

Got that right, whichever one it was. So, okay.

Racing the Ticking Clock

|

| I felt as if Rex and I were racing against time in more than one way (See credits below). |

But if I added a whole new point of view, I’d have to do a major revision. A new POV would require more words, and the book was already running “on the long side.” Worse, I had already hit the date on the calendar when I’d planned to be completely finished with writing A Bone to Pick!

But did any of those objections mean I should stick with the version I had?

No. Of course not. So I sucked it up, hid all the calendars, and took another run at it. The book will be as long as it needs to be, and take as long as it needs to take, became my operating guideline. My objective was to write the best book I could. Any other consideration wasn’t relevant, because it didn’t have anything to do with that central objective.

The Denouement

I guess we’ll soon see how I did.

Early returns from the Brain Trust have been encouraging. Ultimately, we’ll have to see what readers think.

Next week I’ll write about the presale offer. Once the Brain Trust has had their say, I’ll try to get everything finalized so I can send out Advance Reader Copies in July (subscribe to my newsletter, to learn how you can get one!).

The Official Release Date is September 15.

So! When will we see Bone of Contention?

To answer the next question, yes, I’m already at work on the third book of the Trilogy. When will it be finished?

Well, I already have a partial outline. There’s a whole section of scenes I cut from earlier versions of earlier books, that I plan to use in this one. So, it’s partly written already! I should easily have it ready to go in 2022. A year, maybe 18 months, tops, because I know I’m a slow writer.

But seriously. What could possibly go wrong?

IMAGE CREDITS:

BOOK COVERS:

First of all, I owe deep gratitude to my wonderful cover illustrator, Jody A. Lee, who has created both covers for the Trilogy so far. The cover for What’s Bred in the Bone is © 2019, and the one for A Bone to Pick is © 2020, both by Jody. She persevered, even when the undulating terraces and weird perspective of Wheel Two in the background threatened to drive both of us crazy.

A MIRACLE AND GOOD CODE:

Deepest thanks to Sidney Harris and his original publisher, The New Yorker, for the “Miracle equation” cartoon, and to Amor Mundi where I found a decent-quality version of this much-memed classic image (and thanks to the Cleveland Centennial, for guiding me to the original credits). I offer up yet more thanks to Jessie Liu 刘翠 @jessiecliu on Twitter, for the “Good Code” diagram.

DEVIATING FROM THE ROAD:

For the gorgeous shot of the scenic pullout along the Oregon coast, I am grateful to AAA. Moving clockwise on the “Deviating from the Road” montage, I want to thank New Jersey 101.5 for the “Detour” sign, and Andrew Capelli’s Active Rain blog, for the photo of the “Road Ends” sign. I think it metaphorically did all of these things while writing A Bone to Pick.

EVERYTHING ELSE:

Many thanks to Green Car Reports for the photo of the crash test of the unfortunate little yellow car. In the final graphic, I am grateful to Lucy A. Synk for her © 2020 illustration of XK9 Rex at a full-out run, and to Dirk Ercken via 123rf, for the “Time is Running” illustration. All montages were assembled by Jan S. Gephardt.

No comments:

Post a Comment