My mid-week posts this month have been a series of meditations upon what I think are outmoded science fictional tropes, be they ever so time-hallowed. There are just some times and settings in which I can't suspend my disbelief of these extrapolations.

The series was inspired by my thoughts while reading Leviathan Wakes, by James S. A. Corey. Let's get this straight, right off the top: I have some issues with it, but it's still a wonderful space opera, well crafted and thoroughly worth reading.

So worthwhile, in fact, that the SyFy Channel has turned it and the other books of the highly successful Expanse series into a TV show, also called The Expanse, which is in its third season as I write this. In particular, my comments center upon Ceres Station, its population, and its governance, as portrayed in the book.

I compiled a short list of outstanding reasons NOT to live on Ceres:

The series was inspired by my thoughts while reading Leviathan Wakes, by James S. A. Corey. Let's get this straight, right off the top: I have some issues with it, but it's still a wonderful space opera, well crafted and thoroughly worth reading.

So worthwhile, in fact, that the SyFy Channel has turned it and the other books of the highly successful Expanse series into a TV show, also called The Expanse, which is in its third season as I write this. In particular, my comments center upon Ceres Station, its population, and its governance, as portrayed in the book.

I compiled a short list of outstanding reasons NOT to live on Ceres:

- Human life is apparently cheap, and easily squandered with no penalty.

- Freedom of speech is nonexistent, and so is freedom of the Fourth Estate.

- The nutritional base is crap. Seriously? Fungi and fermentation was all they could come up with? Readers of this blog don't need to guess what I think of this idea.

- Misogyny is alive and well, but mental health care is not.

Last week I examined the reasons why I think a highly educated and intelligent work force of relatively few people, supervising lots of robots, were a far more realistic and likely extrapolation than a dense population of "expendable" humanity.

I also said I thought that Silicon Valley and the current aerospace industry--not the coal mines and textile mills of yesteryear--were the likelier model for ideas about what you'd find among workers in space.

Today I want to take on the questions of human rights and quality of life issues--and explain why I think the government of Ceres, as portrayed in Leviathan Wakes, wouldn't have lasted nearly as long as it apparently did, even with Star Helix Security activating in its most fascist mode.

It was never clear to me exactly what sort of governing system Earth supposedly had set up on Ceres (don't look to the wiki for help, either), but it clearly wasn't a representative democracy. Why not? Apparently, we readers weren't supposed to ask or care, and the residents certianly weren't supposed to weigh in on the matter.

Which means it doesn't take a genius to figure out why there might be unrest. Seriously, people! Nobody needed a gang problem (although the form of government certainly might foster one) to foment unrest on Ceres. Heck sake, the quality of the food alone probably set off riots! (remember: fungi and fermentation only. Yeep).

But given the realities I foresee for the "immediate to intermediate future" of space, whether the governing body is a corporate overlord or a government, the days of the “company store,” debt bondage, and indentured servitude would either be a non-starter or at the very least won’t last very long in a realistic future setting.

Rational human beings will recognize those ideas for the royal shafting they are (as they always have, truth be told), and they will sooner or later find a way to overturn it.

I'm extrapolating that only the bright and well-educated will make it into space--the career-driven, who wouldn't know what do do with a baby. But they certainly will know what to do with anyone who tries to mess with their freedom of speech or assembly. How long did the Gilded Age last? Two decades? And they didn’t have the Internet. I’m betting on much, much sooner than later.

But if Silicon Valley is a more likely model than a coal mining company town, we're still not out of the woods--and in that way, the Ceres of Leviathan Wakes is all too realistic: the misogyny in this world is at times breathtaking. I'm writing this on the other side of #MeToo, but this is one battle that is very far from being won, yet.

I haven't read the whole series, so I don't know if the misogyny changes later on--but changing science fiction culture itself to stifle misogyny is not for the faint of heart. If you remember Gamergate, you know what I'm talking about. If you don't click on that link!

All I'm saying is, The Expanse series is supposed to begin a couple centuries on from now. Sisters, if we haven't raised consciousness and kicked some butt by then, God help us!

IMAGES: Many thanks to Amazon, for the Leviathan Wakes cover image; to Fact File for the coal mining photo; to Vox, for the photo of a riot on Ceres from The Expanse; and to Shout Lo, for the "Equality Loading" image. I deeply appreciate all of you!

I also said I thought that Silicon Valley and the current aerospace industry--not the coal mines and textile mills of yesteryear--were the likelier model for ideas about what you'd find among workers in space.

Today I want to take on the questions of human rights and quality of life issues--and explain why I think the government of Ceres, as portrayed in Leviathan Wakes, wouldn't have lasted nearly as long as it apparently did, even with Star Helix Security activating in its most fascist mode.

It was never clear to me exactly what sort of governing system Earth supposedly had set up on Ceres (don't look to the wiki for help, either), but it clearly wasn't a representative democracy. Why not? Apparently, we readers weren't supposed to ask or care, and the residents certianly weren't supposed to weigh in on the matter.

Which means it doesn't take a genius to figure out why there might be unrest. Seriously, people! Nobody needed a gang problem (although the form of government certainly might foster one) to foment unrest on Ceres. Heck sake, the quality of the food alone probably set off riots! (remember: fungi and fermentation only. Yeep).

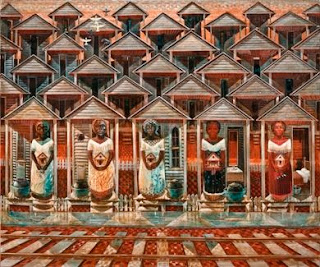

|

| The food alone ought to set off riots on Ceres. Given the abysmal governance, no wonder the locals got restless! |

But given the realities I foresee for the "immediate to intermediate future" of space, whether the governing body is a corporate overlord or a government, the days of the “company store,” debt bondage, and indentured servitude would either be a non-starter or at the very least won’t last very long in a realistic future setting.

Rational human beings will recognize those ideas for the royal shafting they are (as they always have, truth be told), and they will sooner or later find a way to overturn it.

I'm extrapolating that only the bright and well-educated will make it into space--the career-driven, who wouldn't know what do do with a baby. But they certainly will know what to do with anyone who tries to mess with their freedom of speech or assembly. How long did the Gilded Age last? Two decades? And they didn’t have the Internet. I’m betting on much, much sooner than later.

But if Silicon Valley is a more likely model than a coal mining company town, we're still not out of the woods--and in that way, the Ceres of Leviathan Wakes is all too realistic: the misogyny in this world is at times breathtaking. I'm writing this on the other side of #MeToo, but this is one battle that is very far from being won, yet.

I haven't read the whole series, so I don't know if the misogyny changes later on--but changing science fiction culture itself to stifle misogyny is not for the faint of heart. If you remember Gamergate, you know what I'm talking about. If you don't click on that link!

All I'm saying is, The Expanse series is supposed to begin a couple centuries on from now. Sisters, if we haven't raised consciousness and kicked some butt by then, God help us!

IMAGES: Many thanks to Amazon, for the Leviathan Wakes cover image; to Fact File for the coal mining photo; to Vox, for the photo of a riot on Ceres from The Expanse; and to Shout Lo, for the "Equality Loading" image. I deeply appreciate all of you!