As I've been designing a

space-based habitat that is home to the characters in my

"XK9" novels, one of the recurring questions is

how will these people feed themselves?

On the

eve of the US Thanksgiving holiday, it seems an especially apt question.

|

| Space Farmer by Jay Wong: if we're out there, we'll have to eat. |

As you may have picked up from comments I've made in several of my previous "DIY Space Station" posts,

I have some rather pointed views about agriculture in a space-based habitat. I've lived

in or near farm country all my life, and I've been an

organic gardener (I was

even a garden club president once!) for many years. Of

course I have opinions. :-)

One thing's certain:

space colonists will have to eat--and for their habitats to be sustainable, they'll have to produce food where they live. From

Yuri Gagarin's first space meal on Vostok 1 in 1961 and

John Glenn's first meal during the Friendship 7 mission in 1962 to

contemporary experiments on the International Space Station, finding ways to fulfill this basic human need in space has been an ongoing concern.

|

| An agricultural area in Kalpana One, as envisioned by Bryan Versteeg |

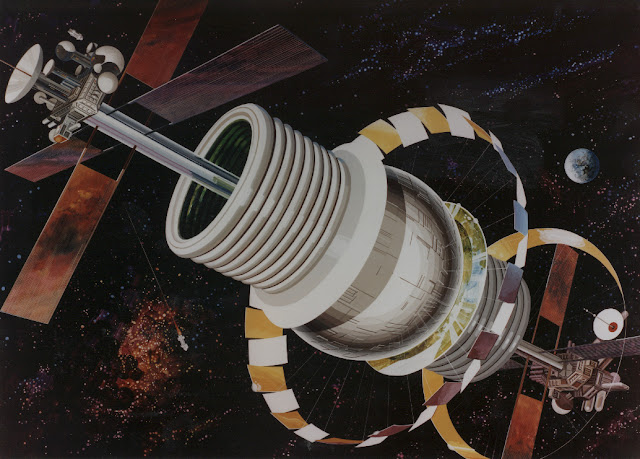

The 1970s-era NASA project designers who created the

Bernal sphere and

O'Neill cylinder designs assumed that

intensive farming, something like the

industrialized agriculture that was beginning to become widespread at the time, would be most efficient for space. They designed

a separate section for agriculture, the so-called

"Crystal Palace" of the

Bernal sphere. The same kind of structure was planned for the

O'Neill cylinder.

|

| Perhaps the "Crystal Palace" made sense in the 1970s. |

I don't know if you've ever been near a

feedlot or

hog farm and smelled the "atmospherics" produced by intensive livestock farming, or if you've ever studied the

health risks,

carbon footprint or

water use of such projects, especially as regards beef, but if you have

the "Crystal Palace" plan should give you pause.

As I explained in

my post on Bernal spheres, we've learned a lot about the perils of such practices since then. There's also

growing evidence that all beef, chicken, salmon, and other meat proteins are not equal: the intensively-farmed versions are markedly inferior. Why ever would we take those methods into space?

|

| Not actually healthy for anybody: cattle on a large feed lot. |

In a relatively small, enclosed system such as a space habitat, everything must be recycled. There'd

only be room for highly efficient agricultural methods. Intensive livestock farming is still

livestock farming--

inherently inefficient, compared to many other protein sources.

Of course, there's a question of

exactly what does "efficient" mean?

During the recent drought, for instance,

California almond farmers have been taking tremendous criticism over their thirsty almond groves. But in general nuts are an

excellent source of protein. In

a smaller, closed system with a controlled water cycle, trees' value must be considered in terms of

the nutrition and oxygen they produce, not only the

water they consume.

|

| Almonds ready for harvest. |

Unfortunately, when you look at nutritional protein sources, animal-sourced protein (including eggs and some milk products) tends to be better-suited for human metabolisms than most vegetable sources. A balance of

both sources is best, nutritionally--but

how do you get meat, milk and eggs in a space habitat where there are no wide-open spaces for healthy animals to roam?

Aquaponics systems can sustain quite a variety of plant crops, but also can produce animal protein from fish, shrimp, prawns, etc. That might provide a partial solution.

|

| An aquaponics "family plot" grows a wide variety of plants. |

Certainly ventures such as Sky Farms in Singapore are pushing the envelope on the potential to grow more food in a smaller "footprint," and they're doing it with aquaponics. But so far they're growing mostly salad greens, not almond trees.

|

| The rotating towers of Sky Farms are designed to make sure all plants get adequate sunlight in a vertical planting scheme. |

Sky Farms brings up another important point: the space station designers of the 1970s envisioned farming as something that happened in separate, "agricultural" areas. Yet contemporary trends are opening us to more urban agriculture options. "Farms" aren't just out in the country anymore. They're popping up in vacant urban lots and in greenhouses on urban rooftops.

|

| This community garden in Kansas City, KS is not far from my home. |

Another recent trend in urban plantings are so-called "green walls," planted with a variety of species to create visual interest, produce oxygen, and help clean the air. I can't imagine those would be hard to adapt for edible plants.

|

| The company that makes this vertical planting system is called--appropriately enough--Greenwalls. |

And of course, space-saving espaliered fruit trees have been around for centuries.

|

| An espaliered peach tree at historic Le Portager du Roi (Vegetable Garden of the King) at Versailles, France |

Another idea gaining traction lately has been "green roofs." One has only to look at Bryan Versteeg's visualizations of Kalpana One to see that I'm not the first person to think of putting them on space habitats.

|

| Bryan Versteeg beat me to the idea of green roofs on a space habitat: this is part of his visualization of Kalpana One. |

In addition to providing pleasant green spaces and oxygen, they'd make ideal garden plots if the soil was deep enough. Urban rooftops all over the world support similar green roofs and rooftop gardens.

If agricultural efforts are integrated throughout the entire space habitat, that changes the picture and the potential. Food could grow anywhere! Why not on pergolas hung with grapevines, squash, or tomatoes, for example?

|

| This is a squash trellis, but lots of food plants grow as vines, which means they can grow up walls and hang from trellises or pergolas--providing yet more vertical growing options. |

And while we might not see cattle wandering freely through the streets, we certainly might find "backyard chickens" or other, smaller-scale livestock growing operations (Rabbits? Goats?) tucked in here and there all over the station--another potential partial solution to the "where do we get our protein?" question.

|

| Beyond aquaponics: could small-scale chicken farming be another source of protein on a space habitat? |

None of this discussion has so far wandered into the areas of genetically-modified plants, that might be specifically adapted for high yields in small amounts of space, but they are likely to be developed, whatever we may think of GMOs (a discussion for a different post).

Another area that's still in its infancy is

cultured meat. Yes, right now

one tough, relatively tasteless patty recently cost about $263,000 to produce, but the Dutch lab that produced it from beef stem cells is anticipating its products could be

commercially available and viable by 2020.

|

| The $263,000 burger, before cooking. Is cultured meat the future of protein in space? |

While the question of how many resources such

"cellular agriculture" might require is still open, it

seems likely that the field will have evolved considerably by the time we're

building habitats in space. So maybe our

descendants who venture forth to live on the Final Frontier won't have to forego eating their favorite Kobe steaks after all.

IMAGES: Many thanks to Jay Wong's website, for his Space Farmer image, to Bryan Versteeg's Spacehabs Gallery for the Kalpana One farm and green roofs images; and to Wikipedia and NASA for the "Crystal Palace" image (sorry--couldn't find the artist's name).

I'm indebted to "Johnny Muck" for the beef feedlot photo, to Grow Organic for the photo of the ready-to-harvest almonds, and to Friendly Aquaponics for the photo of varied crop-plants in an aquaponics system.

Many thanks to Urban Growth for the image of the Sky Farms tower, to Kansas City Community Gardens for the photo of the urban garden in KCK, and to SkyHarvest via Pinterest for the photo of their rooftop greenhouse.

Thanks greatly to Greenwalls Vertical Planting Systems for their photo of a contemporary "green wall." Go to their website for more beautiful examples.

Thanks also to Paully and Growing Fruit for the photo of the espalliered peach tree at Versailles, to Noble Rot of Portland, Oregon, for the rooftop garden photo, to Organic Authority for the squash trellis photo, and to the Denver Library's website, for the photo of urban chickens. And finally, thanks to the Daily Mail for the photo of the cultured meat patty.