By Jan S. Gephardt

In Kansas and Missouri, we’re holding a primary election next week. And every time there’s a primary, some people question whether or not it’s important to vote in it. I’ve blogged about Primary Elections in other years. Longtime readers of my “Artdog Adventures” blog know very well that I feel it’s important to vote.

I realize some of my readers don’t live in the United States, and many others live in states hold their primaries earlier or later in the year than now. I was talking about this with my sister recently. She agrees with me on the importance of voting, although for her the primaries are so last March (she’s a Texan, as longtime blog-followers well know).

But in my neighborhood, the primaries are looming (August 2). It’s important to vote because elections are always a potential turning point of some sort. And that’s where life is informing my art rather a lot, recently.

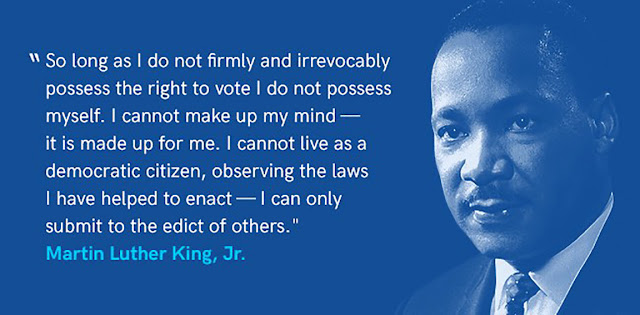

|

| (Image courtesy of Medium). |

Life, Art, and Science Fiction

I’ve already blogged some about politics on Rana Station. Rana is the fictional, far-future space-station home of the XK9s and their favorite humans, the setting of my novels. Readers of my stories may recall mentions of elections for Premier that were held while the XK9s and their partners were still on Chayko. POV characters Pam and Charlie voted absentee, and talked with their XK9s about the elections. It’s unspoken but clear that both think it’s important to vote.

There are political undercurrents throughout the XK9 “Bones” Trilogy. On Rana, Boroughs are sort of a cross between a city and a state or province, politically. Readers saw the local Borough Council in a special session during What’s Bred in the Bone. In the second novel, A Bone to Pick, Ranan politics received less focus. But that realm returns in a big way –on a national level – in the third novel, Bone of Contention. As it happens, I’m writing some of that part now.

Of course, politics in science fiction is nothing new. I’ve been thinking about that a lot, recently.

|

| (See credits below). |

Eroding Rights

Women who pay attention know our rights and freedoms are always under attack. Cases in point: horrifying recent stories about Mongolian schools that require “virginity checks.” Patriarchal cultures use force to suppress education for girls. Invading armies use rape as a means of terrorizing civilians. All across the world our freedom and bodily autonomy are at continual risk, and they always have been.

Even before the United States Supreme Court handed down the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health verdict that made it official, we in the USA saw the warning signs if we were paying attention. Remember “pussyhats” and the Women’s March on Washington in 2017?

As a science fiction reader and writer, I’m aware of many dystopian “futures.” It’s a time-honored science fiction tradition to base dystopias on contemporary trends taken to extremes.

And in nearly any dystopia ordinary people are powerless. They have no agency, no autonomy. Goes without saying they have no vote.

|

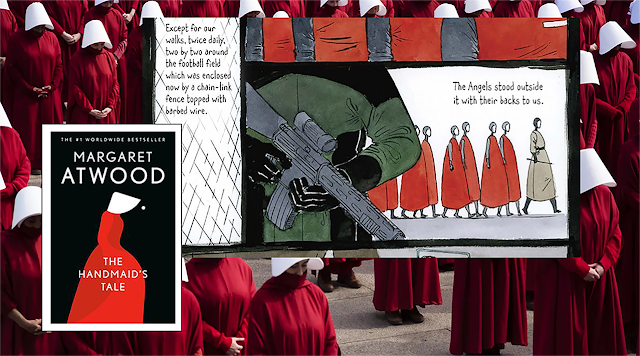

| Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale has been adapted into a graphic novel and a television show. (See credits below). |

Tales and Parables

One science fiction story that has resonated deeply with women – and in the wake of Dobbs feels even more relevant – is Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. In this dystopia, first released in 1985. Starting production in 2016 (imagine that), a television series by the same name, based on the novel, has been renewed for season after season.

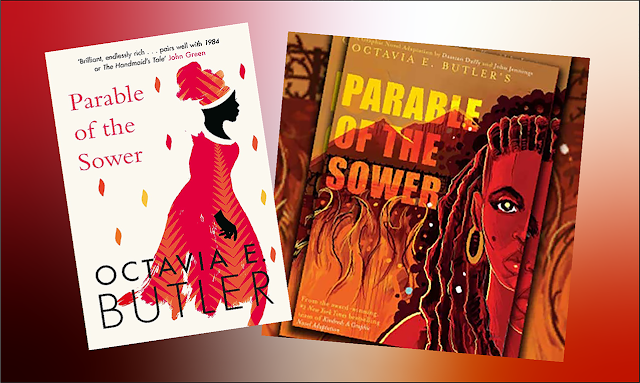

But the science fiction that’s resonating most deeply for me this week is Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower. I’ve been re-acquainting myself with it. I remember when it first came out in 1994. Back then, I was a mother with young children and little time. I had difficulty reading it, probably because I wasn’t ready to contemplate a world like the one it depicted.

Now, in 2022 (the book starts in 2024, in a world both unfortunately like, but also different from our current situation), I’m finding the parallels interesting. Butler’s world, in fact, feels like an oddly familiar place. For one thing, there’s more than a small echo of the assumption I grew up with, that it was only a matter of time before disaster hit. At the age of Butler’s main character Lauren, I tried to learn canning and gardening, assuming I’d need such survival skills after the coming nuclear apocalypse. But there are other parallels, too.

|

| Octavia E. Butler’s book Parable of the Sower has been adapted into a graphic novel and optioned for a film. (See credits below). |

A Different Apocalypse, But it “Rhymes”

The kind of apocalypse Californian Lauren Olamina faces in Parable of the Sower didn’t start with a bomb blast. Some reviewers call the novel “post-apocalyptic,” but that’s not correct. The slow-rolling apocalypse Lauren and her neighborhood face is protracted and actively ongoing. There is nothing “post” about it.

Its origin lies in steadily-chipped-away rights, a process that has disabled all government protections for ordinary people. This has led to savage economic disparity and inflamed racial division. Of course, those dynamics further cripple government. The power and importance of voting has been reduced to choices between bad and worse impotent politicians. But you can only vote if you can make it through the mean streets to the polls in one piece.

By the time of the novel, all the last safety nets of civilization have been stripped away. This dysfunctional dynamic empowers the rise of business behemoths that capitalize on the power vacuum to further entrench their own advantage. No surprise, there’s a massive and growing unhoused and dispossessed population that’s increasingly desperate and lawless.

|

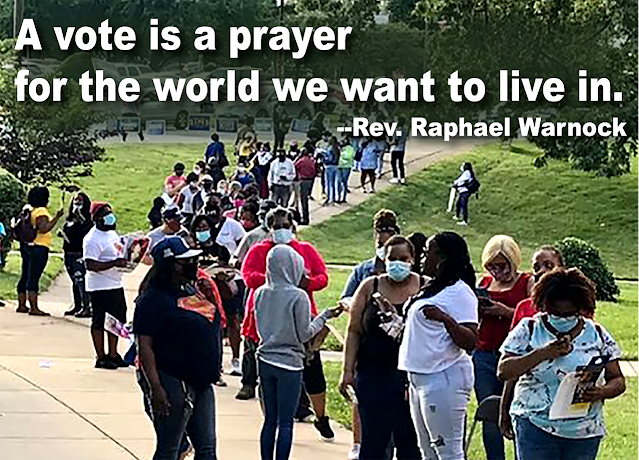

| (See credits below). |

The Antidote? It’s Important to Vote! (While we still can)

Does any of this sound familiar? If not in exact mirroring, it certainly takes little effort to recognize parallel dangers in contemporary gerrymandering and false claims of vote fraud that threaten to actually do the real thing. If it’s okay to declare that corporate “free speech” (AKA money) is protected, and that some people have no right to bodily autonomy, how far from slow-rolling apocalypse are we, truly?

All of this brings me back to the importance of voting. We’re not yet in full-blown apocalypse. We won’t be (barring unforeseen disasters) in 2024. But we’ve been flirting with it for longer than many people have noticed. And if more of us don’t wake up to the serious issues that threaten our freedom and our democracy, we’ll wander blindly into it.

Our rights are increasingly on the line. Our best defense is our vote, and here the advice is “use it or lose it.” That’s why it’s important to vote. Every time. In every election. Vote.

IMAGE CREDITS

The quote-image for Dr. King’s view of the importance of the vote came from Medium. The background for the quote from Jan is Nebula 2, ©2021 by Chaz Kemp, first published in the blog post “Looking for Hope.” Design by Jan.

Jan also assembled the two montage images built around two of the books mentioned in the post. The Handmaid’s Tale montage Includes several images. The cover for Margaret Atwood’s novel is courtesy of ThriftBooks. A page from a graphic novel adaptation by Renee Nault comes via Maclean’s. And a still from the television adaptation of the book is courtesy of Woman & Home.

The montage for Parable of the Sower features the cover of Octavia E. Butler’s book, courtesy of the North Carolina State University Libraries. Butler’s book also has been adapted by Damian Duffy into a graphic novel illustrated by John Jennings. No TV show yet, however it's been optioned for a movie.

Jan first assembled the final quote-image in this post from a tweet by the Rev. Raphael Warnock (now US Senator Warnock) in November 2020. The background photo is originally from the Baltimore Sun, taken at the Maryland primary election, June 2, 2020 by the multitalented Karl Merton Ferron. Deepest appreciation to all of them!