By Jan S. Gephardt

Have you noticed any leitmotifs in your life? I’m using the term loosely here, to describe a phenomenon I’ve observed in many creative lives. But I probably should explain a little. By definition, a leitmotif (pronounce it “LIGHT-mo-teef”) is a recurring theme or thematic element in a work of art.

The 19th century German opera composer Richard Wagner popularized the term—and made brilliant use of the technique. You often hear the term “leitmotif” in reference to music, literature, or film.

For examples, think of the color red in The Sixth Sense, or “Hedwig’s Theme” in the Harry Potter movies (20th-21st century American composer John Williams makes brilliant use of the technique, too).

We don’t usually think of it in terms of visual art but that’s a mistake. Paul Cézanne kept returning to Mont Sainte-Victoire (which he could see from his studio in his ancestral home). It wasn’t the only thing he painted. Far from it! But he kept coming back to it. Mont Sainte-Victoire was a leitmotif in his approach to his work. Many other artists offer parallel examples.

|

| Three decades, three paintings of the same mountain. L-R, Paul Cézanne painted Mont Sainte-Victoire in 1887, 1895, and 1902-4. (Credits below). |

Creatures Built to See Patterns

We humans are creatures built to see patterns. Evolution has crafted us that way. It’s a survival tactic. The bright little hominid who spotted a pattern of sights, sounds and smells that signaled a tasty kind of fruit, or a way to fresh water, or the approach of a predator? She was the one who lived. She survived to successfully rear her babies and carry on her genetic heritage.

In a very deep way, we need to make sense of things. There must be an explanation, we insist. And if one doesn’t readily reveal itself, we’re fully prepared to make one up. It’s how we figure out ways to make our lives easier. It’s how we invent new things. And it’s the origin of our primal storytelling need.

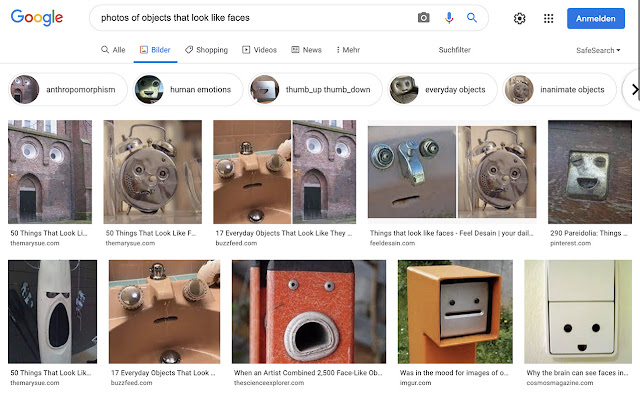

it’s where conspiracy theories, myths, superstitions, and OCD routines come from, too. We’ll readily see patterns, even where there aren’t any. Consider: None of the objects pictured below actually have faces. But most of us see faces, anyway.

|

| Our human aptitude for seeing patterns makes us recognize “faces” on familiar objects. (Google Image Search screen-capture). |

Every Pattern Tells a Story

You’ve heard the saying, “every picture tells a story.” But I’d also say we humans are hardwired to think that every pattern tells a story, too. That’s what makes implied lines work. Are you aware that you see lines where there actually aren’t any? Well . . . of course you do. You just followed two: a dotted line (there is no line, just dots), and a “line” of text.

When you look across a field to a line of trees . . . there are no lines. The crop-growing area stops. Some trees grow nearby. The lines are all in your head. A line of dunes. A line of waves breaking on the beach. Line up, children! We’ll go out for recess, where we might line up a kick to a ball or dream of hitting a line drive to the bleachers.

Our brains make “lines” where reality offers nothing of the sort. It’s all metaphors. That we can make sense of a 2-D drawing or painting—that we can look at a photo montage on a blog post and say, “there are three different paintings of the same mountain"—is a testament to the power of suggestion on a human brain primed to see patterns.

|

| Our brains insist there are lines there, even when they’re only implied. (Credits below). |

Pattern-Recognition

So, then. Have I shaken your confidence in the reality of lines? It may help to remember that your pattern-recognition function is there for important survival reasons. Our bright little hominid’s family eventually produced you—and you aren’t here because all of your ancestors were out of touch with reality.

We may see things that aren’t there—a face in a faucet, or a building with eyes—but we also laugh at those fancies. We have less reason to laugh about other patterns—patterns in our own lives that may signal trouble until we learn to see and adapt to them.

Perhaps you’ve read some or all of Portia Nelson’s There’s a Hole in My Sidewalk: The Romance of Self-Discovery. Her “Hole in my Sidewalk” poem about seeing and avoiding problems in life offers a handy metaphor.

|

| Here’s the poem, “There’s a Hole in My Sidewalk,” by Portia Nelson. (More Famous Quotes). |

In Portia’s poem, the “hole in the sidewalk” can be seen as a pattern of behaviors and attitudes that we’ve developed in our life that repeatedly gets us in trouble. Until we recognize the “hole” for the danger it represents, we keep falling in. People’s “holes” aren’t all the same. For some it may be an addiction. For others, a pattern in their relationships. Or maybe a depressive pattern of thinking.

But if you’re honing your skill at pattern-recognition . . . at recognizing the leitmotifs in your life . . . you’re developing a vital survival tool.

Leitmotifs in My Life

What are the patterns you see in your own existence? What are the leitmotifs in your life? If you need time to stop and think about the question, let me offer an illustration. I’ve already been thinking about this.

One leitmotif I’ve noticed is that I always end up circling back to my sister. We were “first best friends.” We’ve wobbled in and out of each others’ orbits as our lives and careers took us in different directions, but G. is in many ways one of my most important touchstones in life. Whenever and wherever we come back together, we’re still that foundational “us.” Some things may change, but others never do.

My Beloved, Pascal, my husband, hasn’t been in my life quite as long (only going-on-49-years as I write this), but he’s another touchstone who keeps me grounded in myself, even as I try to do the same for him. But people aren’t all there is in the world. And they certainly don’t represent the only patterns in life.

|

| My sister G. and my Beloved, Pascal with me, earlier in our lives. (Family archive). |

Other Leitmotifs Open Insights

I realized that nurturing things—students, children, gardens, companion animals, friends, the environment—is another constant in my life. Kind of a default setting. That’s why I went into teaching. The reason why I wanted kids. It’s how I conduct my life.

Animals, especially dogs, are another recurring theme, for me. Having them around just makes life complete. Not having them around means all of my sensory systems are not in place, and the absence of smaller, furry beings . . . echoes kinda hollow. I don’t like it.

In my visual art, it’s sinuous creatures, curling leaves, and expanding blossoms, literally rising off the page as paper sculpture. It’s maps and earth-from-above, and the ever-unfolding adventure of architecture. In my written art, it’s love, family, community—the work of finding a way back together after being pulled apart. It’s lovers and partners protecting each other. Finding hope. And building a way out of darkness. (And dogs).

|

| These details capture recurring imagery in Jan’s paper sculpture (images are © 2013-2021 by Jan S. Gephardt). |

Leitmotifs in Your Life

But that’s me. What about you? What patterns keep cropping up in your life? Which ones are your good-and-true touchstones? Which patterns have you learned to dread and shun? What invariably fills you with joy? To what things and places do you keep returning, because you just can’t stay away?

I pray that for you they are the solid and true things. Things that nurture insight. Perhaps they’re painful things. But if they teach you about yourself, and how to live more genuinely in your own true skin, they’re golden.

You may or may not want to share them in the comments below. If not, no problem: this got personal. But if you’ve realized or recognized again that there’s a pattern in your life that you’d care to share, please do!

IMAGE CREDITS:

Many thanks to Smart History for the images Mont Sainte-Victoire (1902-04) and Mont Sainte-Victoire With Large Pine (1887), and to WikiArt for Mont Sainte-Victoire (1895), all by Paul Cézanne. I appreciate Google Image Search for the results from a search for “Photos of objects that look like faces” (my screen-capture).

All gratitude to Ms. Dodge’s Website, “The Elements of Art” page, for the instructional chart showing examples of actual lines versus implied lines. I totally love Matt Fussell’s lesson “Losing Lines in Drawings” on The Virtual Instructor, and his great example with the skull and shadows. And I was utterly delighted to share Malika Favre’s “The Leftovers,” a master class in implied lines. It came from Design Culture, found via Erika Oldershaw’s wonderful “Implied Line in Art” Pinterest Pinboard.

Many thanks to More Famous Quotes and its “Hole in My Life Chapter Quotes” page, which gave me a great visual for Portia Nelson’s wisdom. The photos for the montage featuring G. and Pascal in my life all came from the family archive. And the examples of Jan S. Gephardt’s paper sculpture are all © 2013-2021 by Jan S. Gephardt.

No comments:

Post a Comment