“We can’t market this” is a reason for rejection that I’ve heard for decades. It says “your book/story doesn’t fit into our pre-made boxes.”

Innovation is sometimes the stuff of new bestsellers, although I’d argue that a book’s worth isn’t always or only revealed by its sales figures. But it admittedly is much harder to sell square pegs when your marketing is solely designed to appeal to round holes.

Gatekeepers

The literary world is famously full of multiply-rejected books that later became bestsellers considered classics. But you also might note that their authors, once they finally were published, overwhelmingly tended to be White, and predominantly (though not exclusively) male. This begs the question of who, outside of this privileged subset, can write risky things that eventually are allowed to succeed to their potential.

Whenever we talk about access to markets (and to marketing dollars), we must talk about gatekeepers. In the US today, we’re still having that conversation, because our gatekeepers remain overwhelmingly white, and predominantly male.

It shows up in the bestseller lists. It shows up in the ethnic makeup of mainline publishers, and famously in the Oscars, and the projects that get the largest budgets.

Family stories

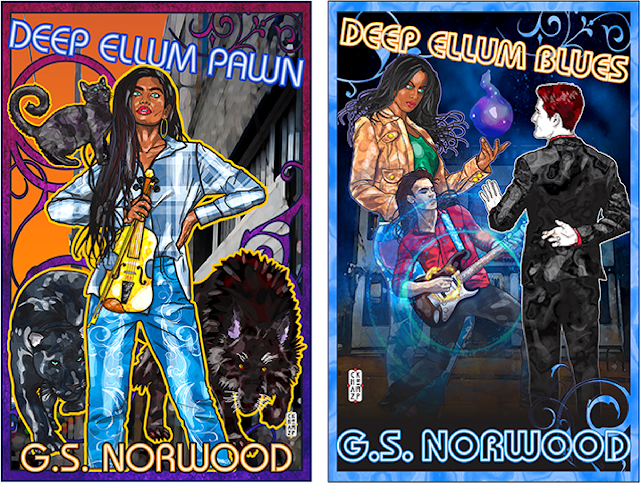

The idea for this post began during a recent conversation I had with G. S. Norwood. She wrote a collection of novels during the 1990s that racked up persistent rejections. The editors to whom she submitted them generally thought they were great stories, well written, and with wonderful characters—“but we can’t market this.”

This was a period when the hottest (and by far the biggest) market was in romances. G.’s novels tried to be romances, but in one way or another they didn’t conform to the expectations of the market. She’s now reviewing them, and revising as she sees the need. We’re preparing to offer them as contemporary women’s fiction, the niche where I’ve always thought they belonged.

We have another family story related to this topic of gatekeepers and markets. One of Warren C. Norwood’s last novels, a story deeply rooted in Chaos Theory, apparently confused the editors to whom he pitched it. They might be science fiction editors by title, but they also were recent graduates of Vassar and Brown. Their intellectual roots sank deeper into English literature than into the mathematical modeling of dynamical systems.

A couple of decades later, another nerdy novel, The Martian, started out as a blog, then became a self-published ebook, and eventually went on to far more fame and movie rights than it might have had, if there’d been more gatekeepers in play.

Contrast the story of American Dirt, which still persists on Amazon Top-100 lists, despite its inauthenticity.

Self-serving excuses

“We can’t market this” is the classic excuse of the misogynist, the racist, the classist, the formula-slave, the gatekeeper who has outlived his/her usefulness.

It’s the excuse that has dictated decades—no, centuries—of whitewashing. I remember back when the complaint was that “female protagonists don’t sell.” “Black/Latin/Asian/LGBTQAI+ protagonists won’t sell.” “You can’t put a black/Latin/Asian in a central position on the cover because it won’t sell.” This, of course, is all hogwash.

But it banishes women, and all persons of color, from leading roles, cover imagery, and headliner status. Oh, and purely coincidentally of course, it preserves male, White, dominant-culture privilege. I mean, really. Can white dudes help it, if they wrote all the truly great literature, and painted all the great art, while everybody else just couldn’t measure up?

Yeah, right.

This is the mindset that left Artemesia Gentileschi "undiscovered" by the wider public until recently. It's the kind of erasure that goaded Mary Ann Evans, AKA George Elliot, to use a male pen name. And it's the mindset that inspired Borders Books (remember them?) to put the African-American romance books way back at the back of the store, far removed from the White romances. Those got more central display.

Myths and prejudices

The myth persists (despite plenty of examples to the contrary) that Black, Asian, or Latin main characters, starring actors, and even book cover characters, don’t sell as well as those featuring White people (Just don’t try to convince Black Panther of that).

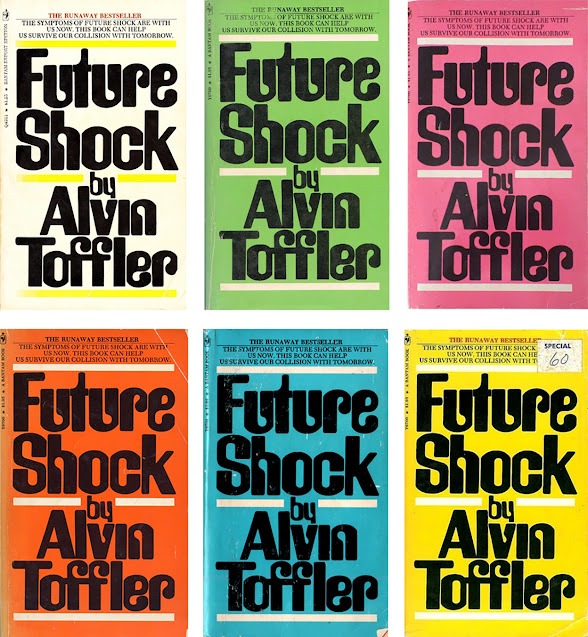

It reminds me of the “green book covers don’t sell” myth, purportedly based on sales of Future Shock, a pop-psychology phenomenon of the early 1970s (yes, I really am older than dirt). The publishers billed it as “a study of mass bewilderment in the face of accelerating change.” I remember people talking about it more as “that book about how we have too many choices.”

It was published in covers of six different colors in 1971 (woah, man, so meta). According to some study somewhere, the green cover sold less well, so it became a “thing” for a while that green covers don’t sell. But then life moved on. Eventually people figured out that beautiful and dynamic green covers actually sell just fine. Who could have seen that coming?

Gatekeepers and Awards

We already mentioned #OscarsSoWhite. An Academy Award has long been considered a pinnacle of achievement (and bankability) within the movie industry. Any theatrical professional locked out of the chance to receive one is automatically barred from the top echelon on the profession.

The Edgar Awards

Literary awards have followed a similar trajectory, because they also purport to be about quality. Prejudices persist, and sometimes that doubles up on the gatekeepers. One case in point: the Edgar Awards. These are the most prestigious awards in mystery writing, but the gatekeeping is notably strict. According to the rules:

“All works submitted for consideration must meet the requirements for Active Status membership as described in the membership guidelines. At this time, self-published work is not eligible for Edgar Award consideration.”

The requirements for Active Status membership in Mystery Writers of America reinforce a narrow list of publishers considered “good enough” to warrant membership. It also places would-be MWA members (and potential Edgar nominees) at the mercy of whatever the gatekeepers think is appropriate.

Does that guarantee higher quality? Maybe. Does it enforce a certain homogeneity? That’s much more likely.

The RITA Awards

The Romance Writers of America have far more inclusive membership requirements, but that hasn’t kept them out of trouble. Controversy over the non-inclusivity of their RITA Awards nearly tore the organization apart last year. (The RITAs are no longer being awarded).

|

| Image courtesy of Vox. No illustrator credited. |

Science Fiction and Fantasy Recognitions

The Nebula Awards of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America (and SFWA membership requirements) are much more open to a variety of backgrounds.

But science fiction’s even-more-famous Hugo Awards fended off a different kind of gatekeeping attempt. a few years ago. The self-styled “Sad Puppies” tried to hijack the Hugos, and thereby stifle more diverse voices. They presented themselves as a threat in 2015 and 2016, but ultimately failed. Turned out the Force—not to mention SF & F fandom—just wasn’t with them.

Nor was it with the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer, after Jeanette Ng had her say about Campbell’s racism, misogyny, and imperialist sympathies. It’s now the Astounding Award for Best New Writer, embracing an inclusiveness Campbell himself would never have imagined or countenanced.

Beyond Gatekeepers

Traditional publishing and prestigious awards will always, by their nature, have gatekeepers. People whose inclinations and imaginations are limited by “we can’t market this” remain a fact of life. There also are only so many projects any publisher can fund.

I think Indie publishing (independent publishing) is today’s best answer for silenced voices and authors with smaller (but no less vibrant) niches. Other avenues may open in the future. But for now, here's a venue where new niches can open and new voices seek out an audience.

It’s very far from an easy path to success. Those gates are darned heavy. When you move away from having others market (or not market) your work, there’s suddenly a lot to learn. You may not hear “we can’t market this” from others, but not everything finds a market. Not everyone (in fact, not most “Indies”) can learn to thrive as entrepreneurs-of-necessity in the independent publishing world.

Can you market this?

Taken overall, self-published writers release a fair amount of dreck each year. Many haven’t done their due diligence, or haven’t learned their craft. Maybe they grew impatient with apprenticeship. Took critiques too personally, and stopped seeking them. Maybe they wearied of rejection after rejection, or couldn't wait through the long turnaround-times of traditional publishing. Perhaps they published something simply to say they’re an author.

But a lot of writers do have great stories to tell, and strong writing skills. Some have previously been published traditionally. But all, for any of a range of reasons, found the experience unsatisfactory.

It's possible the gatekeepers didn't value their visions and their voices. Maybe they were pigeonholed as "just a midlist writer," and therefore not worth promoting much. Perhaps they heard, “too niche,” or “too far off-genre” just a few too many times.

Or perhaps they heard, “We can’t market this” too often, as my sister did. These days, that doesn't have to be the final verdict. Independent publishing enables writers to test that “can’t market” analysis for themselves. Maybe it’ll turn out they can market "this," after all.

IMAGE CREDITS:

Many thanks to the "Cold Call Coach" website, for the visualization of gatekeeping, and to the "Fonts in Use" blog, via Goodreads and Amazon, for the image of all the 1971 Future Shock covers. G.S. Norwood provided the "Pensive Warren C. Norwood" photo (thanks!). We're grateful to Vox for the illustration of the broken RITA Award, and the informative article that came with it. And finally, many thanks to the artist "WiseWizard" via Steam, for that evocative image of opening formidable gates.