By Jan S. Gephardt and G.S. Norwood

They say that the winners get to decide whose history—that is, whose version of history—becomes the “official history.” But when it comes to the so-called “Lost Cause,” that isn’t necessarily so.

|

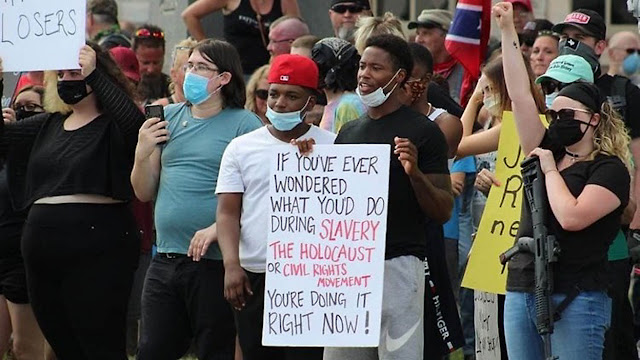

| Photo courtesy of the Milwaukee Independent. |

The pro-slavery South has got to be working some kind of North American record for being persistent sore losers. They’re certainly not the only ones to hold a long-term grudge in world history, but they’ve hung in there for more than 150 years.

Who was it again, that lost the Civil War? Yes, well, we all know denial isn’t only a river in Egypt.

History and the First Amendment

Jan has written a lot of blog posts this summer inspired by the First Amendment. Since the rise of the Black Lives Matter protests, these rights have been on her heart.

Especially so, because the clashes turned violent. Violations of freedom of expression, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly and petition were thick on the ground this summer. We can’t afford not to pay attention.

|

| Photo by Pat McDonough/Louisville Courier-Journal via CNN. |

The renewed calls to take down Confederate monuments are a topic we haven’t tackled till now. For every call to remove them, others cry “you can’t erase history!” But when it comes to issues of erasure and representation, we’re not sure the sympathizers with the “Lost Cause” understand.

They don’t realize that ideologues such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy—who put up many of the monuments—were actually the ones who rewrote, and erased, important parts of our collective history.

The question of whose history we represent—and whose history we erase—is a modern-day minefield where the rules are changing almost as rapidly as the demographics of this country.

A case study in Parker County, TX

A recent episode illustrates some of the complexities of this problem. As she wrote to Jan recently, reports from Weatherford struck home for G., who lived in Parker County, Texas, from 1985 through 2010.

|

| Photo by Charles Davis Smith, FAIA, via Reddit Snapshots. |

“Twenty-five years. I liked the people I met there. They were smart, kind, generous people. Quick to volunteer money and time to worthy causes, they still believed in community groups like the Lions Club and the Masonic Lodge.

“They served on boards, organized rodeos, trail rides, and scholarship funds. They gave high school kids their first jobs, and made sure seniors citizens had hot lunches, affordable housing, and a nice place to go to socialize every day. There were black and Hispanic officers on the local police force and the regional Department of Public Safety (highway patrol) roster. Everybody turned out for the annual Peach Festival.

“I won’t pretend there wasn’t racism. I am white, so I probably didn’t see as much of it as the black professionals I worked beside, but I’m sure it was there, simply because it’s everywhere—especially in states that once belonged to the Confederacy.

The monument on the Courthouse grounds

“A generic stone statue of a nameless Confederate soldier had been placed on the Parker County courthouse lawn by the United Daughters of the Confederacy sometime in the past. Not a work of fine art—just a statement about the county’s history. And apparently its present reality, too.

|

| Photo by Dreanna L. Belden/University of North Texas “Portal to Texas History.” |

“I moved away from Parker County in July 2010. Almost exactly ten years later, on July 25, 2020, some local progressives decided to up their ongoing battle to remove the Confederate statue by leading a small protest march.

“Some sources say there were about 25 Black Lives Matter marchers making their way up South Main to the courthouse square in Weatherford that afternoon. Some estimates go as high as 50.

The counter-protest

All news sources agree that the crowd of counter-protestors who met them was nearly ten times bigger—anywhere from 250 to 500 people.

|

| Photo by Walt Burns/Spectrum News. |

“The counter-protesters came with Confederate Flags. They came with signs, denouncing the Black Lives Matter movement. And they came with guns. One guy even mounted a semi-automatic assault rifle in the back of his pickup truck, military style.

“There was a lot of yelling, some pushing and shoving, and three people were arrested. One of them turned out to be a white supremacist leader from Utah. Nobody was injured, but I was appalled.

I had loved Parker County. Loved Weatherford. Made it my home for many happy years. Never in all that time did I suspect that such ignorance and hatred lived just under the surface. I still don’t know how to process it.”

It’s a lot to process. But that question of “whose history?” certainly comes down to some very personal history. As it is many places, it’s deeply personal for many in Weatherford.

Whose history is important?

Some people, like Kim Milner, who grew up in Weatherford and started a petition to keep the statue, call themselves “Those who want to keep the monuments that reflect our history rather than tear them down.”

But “That Lost Cause propaganda,” as protester Courtney Craig called it in an interview last June with CBS 11’s Jason Allen, has drowned out all other historical perspectives for decades.

Doesn’t mean those perspectives went away, though—or aren’t real.

|

| Photo by Walt Burns/Spectrum News. |

Tony Crawford, one of the organizers of the Parker County protesters, told Spectrum News, “My family was lynched on that square,” he said. “I’m going about this knowing full well that after that statue comes down, it may be too dangerous for me to ever step foot in Weatherford again.”

History’s context

Whose history do we value? Whose history do we preserve? Jan and G. believe that history’s lessons are the most rich and meaningful when we remember the voices, thoughts, and memories of all who had a stake in the events of the times.

That means not glorifying any single narrative over all the others. It also means placing things in context. And sometimes that means removing them from one place to another. Along with Courtney Craig, we believe that there may be places where Confederate monuments could be displayed. Confederate cemeteries, perhaps. Museums.

We do not, however, believe that monuments placed years after the end of the Civil War and intended as propagandistic declarations of domination by “Jim Crow” racists should remain on their pedestals overshadowing public spaces. Or stay in places where justice should be upheld.

IMAGE CREDITS:

All of our image sources come from great online articles and other sources that will reward you if you’re interested in learning more. Please dig deeper to your heart’s content. Many thanks to the Milwaukee Independent for the photo of “Lost Cause” books and memorabilia.

We also want to thank photographer Pat McDonough, The Louisville Courier-Journal, and CNN for the photo of John B. Castleman’s equestrian statue being removed from Louisville’s Cherokee Triangle. There’s a video of the removal in the Louisville C-J article, and an in-depth, illustrated list of other removals in the CNN article.

We’re grateful to Charlies Davis Smith, FAIA, via Reddit Snapshots, for the amazing drone shot of the Parker County Courthouse. And we’re also indebted to Dreanna L. Belden and University of North Texas “Portal to Texas History” for the photo of the Confederate monument at the center of the Weatherford controversy.

Double thanks to Walt Burns and Spectrum News for the two photos from the Weatherford protests, both the “Jail Transport” and “You’re doing it right now!” images. They really captured the range of ideas on the march that day.

And finally, we appreciate Mitch Landrieu’s words about the place of Confederate monuments in New Orleans today, made available via the beautifully-produced video from the Atlantic and YouTube.

Many thanks to all!